I set a goal this year of trying to write more and this Substack is my first effort (better late than never!). I honestly don’t know what I’ll write about. The goal is simply to write and crystallize some of my own thinking in the process. I imagine it will be a bit about the venture ecosystem and a bit about investing.

[No. 1] Understanding Portfolio Construction

One thing that emerging managers are often tasked with is building a fund model. LPs often ask for a fund model because it forces a manager to think through portfolio construction including fund size, number of investments, ownership percentages, reserve ratios, management fees, recycling, etc.

I've probably looked at 100+ models in the past few years and the level of sophistication varies as you might imagine. There is no magic to building a model and LPs are not assessing your mastery of Excel. However, LPs do want to make sure you have a firm understanding of how the inputs and variables impact your ability to produce venture-like returns. Portfolio construction is one of the key inputs in answering the most important question for LPs:

What do I need to believe for this Fund to achieve venture-like returns?

*Venture returns are a topic for another day. For now, let us assume 3x net TVPI (total value to paid-in) is the hurdle.

There aren't a lot of great resources on the web about building a model, especially one that is dynamic, which can be a really difficult undertaking in Excel or Google Sheets. The best resource I have found is Hadley Harris' (Eniac Ventures) post “Seed Fund Portfolio Construction for Dummies". I highly recommend reading his post if you haven't already as he goes much deeper into every aspect of portfolio construction. He also provided a detailed Excel model and some great commentary based on their own experience with Eniac. Every emerging manager should spend time reviewing his post.

Even though I look at a lot of models it is often hard to figure out how different inputs (fund size, initial check size, median entry valuation) and variables (reserve percentage, dilution, graduation rates) impact overall fund returns as it takes a lot of cycles in Excel or Google Sheets to produce a useful sensitivity analysis.

Enter Causal (causal.app). Causal is a "new way to think and work with numbers" founded by Taimur Abdaal and Lukas Koebis. I think of it as a "no-code" platform for VBA and Excel. Causal lets you build uncertainty into any model and then create visual dashboards to share with your team. It’s an awesome product backed by Passion Capital and Coatue.

As I was navigating Causal I decided my first use case was to understand the impact of reserve strategy and dilution on venture returns. The end result of a few hours of using Causal was a Venture Fund Model that I thought I would share. I’ve got a couple of other use cases in the works too. On to the Fund Model.

The Venture Fund Model.

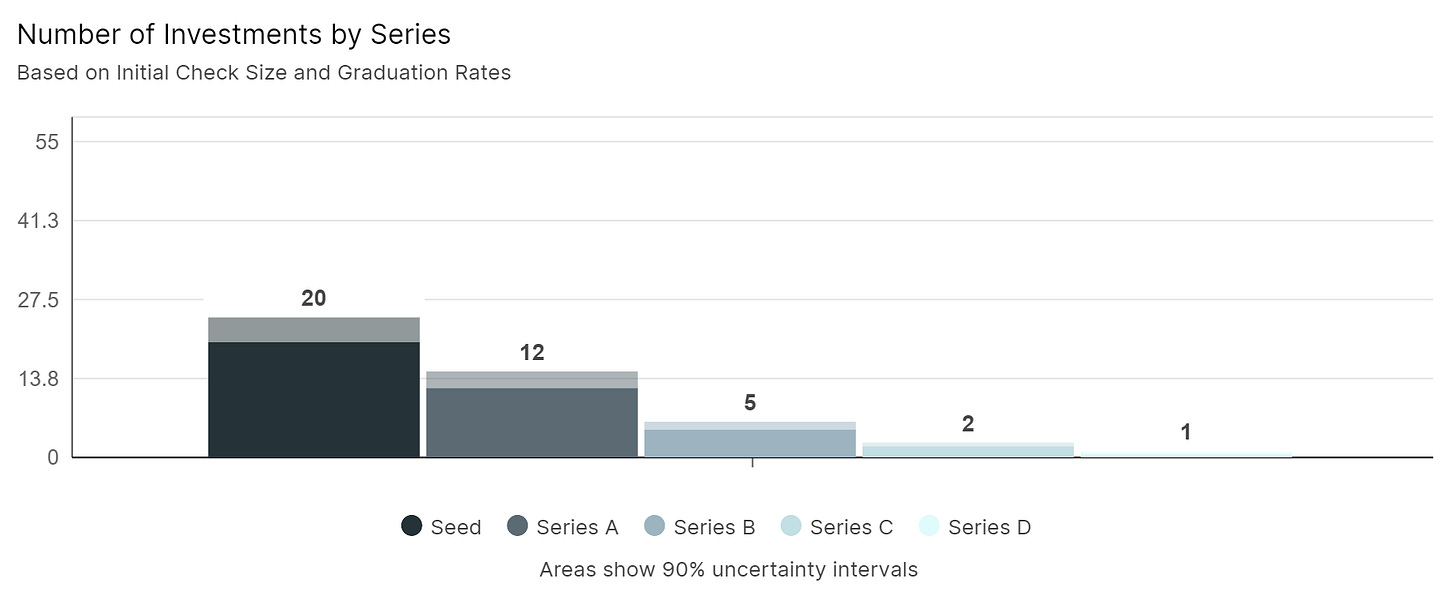

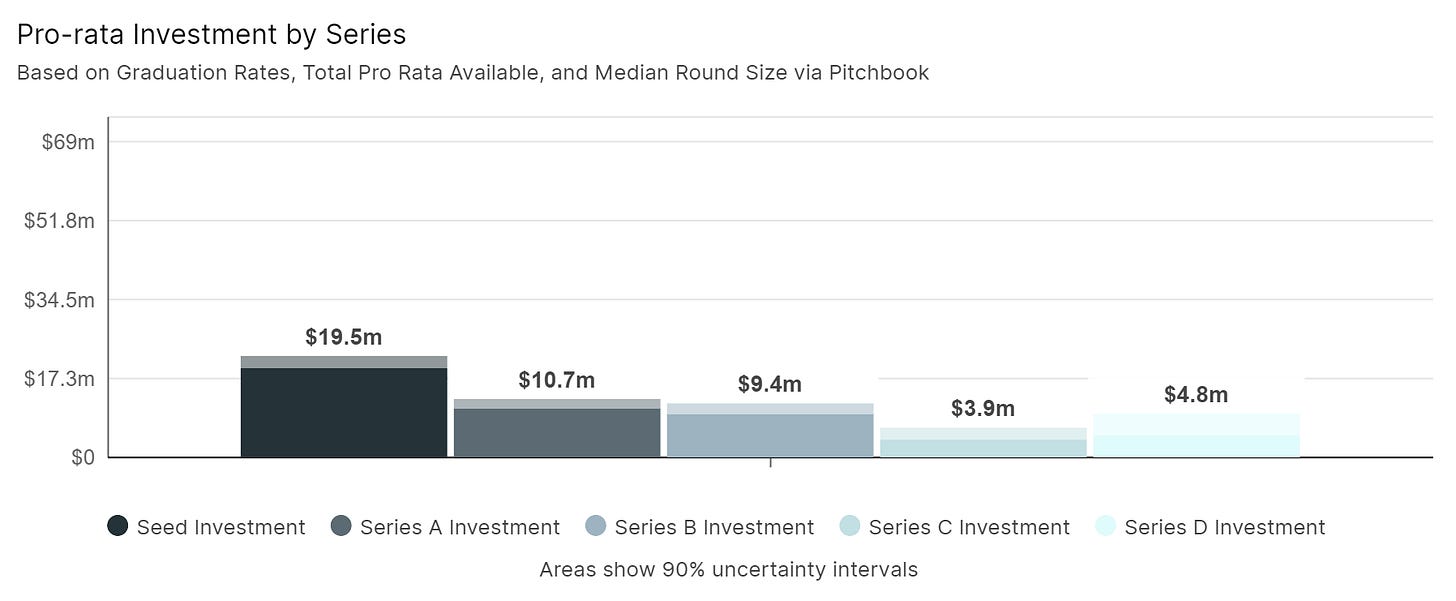

The Venture Fund Model allows the user to input a fund size, initial check size, reserve percentage, and a gross TVPI. The default is a model for a $50 million seed fund but you can certainly adjust the inputs and Series names to reflect other strategies. For this post, I’ve assumed a relatively concentrated seed portfolio with 20 companies, a 1:1 reserve ratio, and a target initial ownership of 10% on average. Because Casual is dynamic you can adjust these assumptions to fit your specific strategy whether you are aiming for a low ownership-diversified fund or a high ownership-concentrated fund.

As you can see below, Causal will provide ranges for outputs that are dependent on other variables. For instance, the number of initial Seed investments is dependent on initial check size and reserve percentage, and median ownership by series is dependent on post-money valuations, round sizes, recycling, reserve percentage, and graduation rates.

So why does all this matter? This matters because there are multiple paths to generating venture-like returns and managers need to understand how their skill set maps to portfolio construction (more on this in a future post). For now, think of it this way. If you model a 1:1 Reserve Ratio then roughly 50% of your total invested capital will be deployed at Series A and Series B. LPs will likely have questions about your ability to assess, and price, product-market fit risk as well as your ability to maintain pro-rata ownership in highly-competitive rounds. If you have modeled a 2:1 Reserve Ratio then LPs might focus more on your deal flow or ability to assess founders (i.e., pick) at Seed. I personally don’t believe there are right or wrong answers to these questions. LPs will often ask simply because they want to understand your thought process and strategy. But you can start to see how portfolio construction and the narrative are tied together.

What do I need to believe to generate a 5x gross multiple?

The math on what you need to believe is pretty simple. I always frame it in terms of total enterprise value required to generate a 5x gross multiple. Simply multiply the fund size by 5 and divide that number by the fully-diluted ownership at exit to get the total enterprise value. Simple math: a $50 million fund with average fully-diluted ownership of 5% at exit needs to generate roughly $5 billion of enterprise value. No small feat!

But as I mentioned previously, there are multiple ways to win (i.e., do you believe you’ll have above graduation rates w/ multiple $1+ billion outcomes, do you plan to have abnormally high ownership in 1 to 2 $1+ billion outcomes, or are you playing for a $5+ billion outcome?).

The charts below I think are helpful in explaining what you need to believe in the modeled scenario:

Takeaway #1: Recycling is important. There is no shortage of experienced VCs who have written about the merits of recycling management fees (Brad Feld, Fred Wilson, and Roger Ehrenberg). The high level is that if you don’t recycle management fees, and management fees run at least 2.0% of committed capital for 10 years you are only investing 80% of the fund. Put differently, as much as 20% of the fund is a complete write-off. Causal brings it to light as the Limited Recycling scenario results in an additional $500 million of enterprise value to achieve a 5x gross TVPI in the Default scenario.

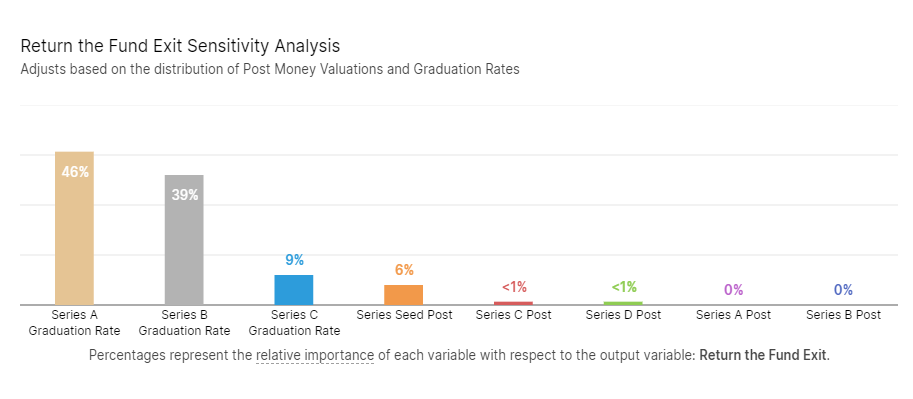

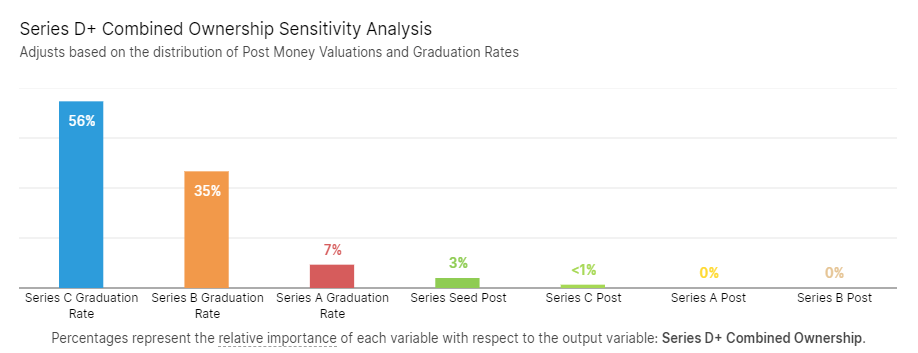

One of the other really useful features of Causal is that it gives you the ability to understand the relative importance of each variable with respect to a specified output variable. The examples below are based on the Return the Fund Exit and the Series D+ Combined Ownership (Series D+ ownership x # of Series D companies). The latter output measures the trade-off between hit rates and pro-rata investment.

Takeaway #2: Entry price matters, but so does your hit rate. It’s a bit obvious that an important variable in the Return the Fund Exit is the post-money valuation and the corresponding ownership at Series Seed. The chart below is Return the Fund Exit Sensitivity if you assume a fixed 60% graduation rate between Series.

Honestly, the whole discussion about whether price matters could be a post in of itself. Yes, it doesn’t really matter whether you invested in Uber at $5 million or $10 million pre-money on a $50 million fund, but it does cut your return in half. Across a portfolio, average entry price matters A LOT. Listen to Josh Kopelman at the 2020 Upfront Summit (Link)

“There are two things that matter in venture. The price you get in at and the price you exit at.”

Of course, you can offset entry price with two things: higher exit valuations as Josh notes or a higher hit rate (i.e., more companies that achieve large outcomes). It reminds me of something one of the best VCs I know once said:

“My ability to pay a high price is a function of my hit rate”

Takeaway #3: Proper reserve management is important. What is less intuitive in the sensitivity analysis is that because the model assumes you follow-on in every subsequent round, a higher Series A Graduation Rate (typically a positive early signal) can exhaust your reserves resulting in greater downstream dilution without a corresponding increase in downstream graduation rates or exits. For example, if you only increase Series A graduation rates from 60% to 80% the Return the Fund Exit increases from $563 million to $688 million in the Default scenario because of increased dilution in later rounds. My guess is this dynamic has tripped up a few managers in the past several years as graduation rates were higher than modeled at Series A and some may have been less discriminating when it came to follow-on investment decisions — dramatically decreasing their follow-on capital and eventually resulting in greater dilution in their winners. In this example, higher Series A graduation rates are not always positive.

Of course, your graduation rate across the board can increase such that you have more Series D+ companies with slightly lower ownership. Series D+ Combined Ownership Points is one way to explain this dynamic. If you assume a 40% graduation rate between rounds in our Default scenario you would have a portfolio of 1 Series D company with avg ownership of 9.3% (~9 pts of total ownership). If you increase graduate rates 20 pts to 60% then you would have a portfolio of 3 Series D companies with avg ownership of 6.9% (~27 pts of total ownership).

This is just one example of how understanding a fund model and portfolio construction can impact returns.

[A v2 of the Seed Fund model might allow for multiple paths (i.e., pro-rata, super pro-rata, pass) at each subsequent financing and include round extensions. I’m tapped out on the number of variables with the free version of Causal.]

Performance.

The last piece of the model is tying it all back to performance. And I should note that this part of the Fund Model is admittedly very top-down.

In the model, a 3 to 4x gross TVPI yields a 2.85x net TVPI on average

Takeaway #4: See Takeaway #1. Recycling is important. LPs can’t spend gross returns. Net returns are all that matter. Cash net returns are even better. Recycling as much as possible dramatically reduces your gross-to-net drag.

Conclusion.

Your fund model is intended to be a guide and a point of discussion with potential LPs. That’s it. There will always be edge cases and an ever-evolving investment landscape so I can assure you that your portfolio will probably look very different than whatever you modeled at the outset. I think Hadley put it best in his post:

“Over time we’ve come to appreciate that portfolio construction needs to be optimized throughout a fund’s lifecycle as projections are replaced by real data”

Portfolio construction is largely a theoretical exercise but what is most important is that you understand how all the pieces fit together and impact your ability to drive returns. It all ties back to the most important question for LPs: What do I need to believe for this Fund to achieve venture-like returns?

Venture is a really hard game. The unfortunate reality is that the vast majority of funds will fail to achieve venture-like returns and many will fail to outperform even the public markets given the headwinds of a “2 and 20” structure. However, LPs continue to invest in the asset class because it has the potential to produce outsized returns. LPs investing in your fund need to believe your portfolio construction has that potential. In a future post, I plan to expand on how to sync your portfolio construction with your overall narrative.

This post ended up being longer than I intended and I’ll certainly explore some of these topics in greater detail in future posts. For now, here are what I think are the key takeaways:

There are multiple paths to generating venture-like returns.

Managers need to understand how their skill set maps to their portfolio construction.

Achieving venture-like returns is no small feat.

Recycling management fees is a key lever in generating venture-like returns.

Entry price matters, but so does your hit rate.

Proper reserve management is important.

Let me know if you have any thoughts, questions, or features you would like to add to the model.

Disclosure: I’ve tried to find as many errors in this model as possible. I can promise you there is something I missed. Please use this with caution and let me know if you find any bugs.

Thanks to Jaclyn Hester at Foundry Group, Aram Verdiyan at Accolade Partners, and Rick Zullo at Equal Ventures for reading drafts and providing feedback on this post. And special thanks to Nikhil Basu Trivedi for the inspiration and thoughtful feedback.

Please check out my website here and subscribe to my Substack for future posts.

This is one of the best-crafted thought pieces on portfolio construction I have come across.

I look forward to more around this topic