[No. 4] Track Records

How I think about them and do they matter?

This post is more of a draft than I would like, unfortunately, but there is a point here that I’ve wanted to flesh out for a while. Maybe it is a simple observation with a slightly different audience. I don’t know. But the early feedback on the draft was constructive so I thought I would put it out there to see what comes back. On to the post…

Track Records

Why am I writing about track records? Well, venture capital has had a tremendous couple of years on the backs of several successful IPOs such as Snowflake, Coinbase, DoorDash, Airbnb, Roblox, Robinhood, Coupang, and others. In short, if you had exposure to high-growth technology companies the last decade the chances are you’ve done really well. This is great for the ecosystem, but it makes distinguishing the signal from the noise even more challenging for LPs.

For many LPs, track records are a core part of their evaluation. The dispersion of returns in venture capital is significantly higher than other asset classes, the ability to consistently identify top quartile funds is crucial to building a world-class venture program. It’s why most LPs focus on track records and why buried in most investment memos you’ll find a chart that looks like the one below.

Plus, there is academic data that suggests there is strong persistence in venture capital returns (i.e., top-quartile funds are more likely to achieve future top-quartile performance) which reinforces a lot of the conventional wisdom in the asset class.1 I think that narrative is changing, but the idea is still pervasive throughout the LP community.

So let’s start with a provocative question…

Are Track Records meaningless?

I think about this question a lot at this point in the cycle. We are all guilty of ascribing too much value to track records. After all, we are “outcome junkies” according to Annie Duke.2 The easiest way to find comfort in a decision is to highlight past results — it is simply hard to argue with data.

Now track records aren’t completely meaningless — although as we get further and further into this cycle there is certainly more noise. There is this great quote from Annie Duke that sums up how I think about them:

The direction in which the chips flow in the short term only loosely correlates with decision quality

Track records over long periods of time more closely correlate with decision quality. I think it looks something like the “S-curve” below (h/t to Laura Roller for helping me think through this). We can debate the point at which the line crosses from noise to signal but it’s a steep curve and certainly plateaus.

For venture capital, my guess is that the track records start to convert from noise to signal around 10 to 12 years (4 to 5 fundraising cycles in the current climate). The general idea is that there is more signal as time increases. For instance, Sequoia Capital has performed for nearly 30 years so it is a decent assumption that their decision quality as a firm is extremely high. More importantly, that track record of success has even more signal given the very different investing climates, technologies, sectors, and market dynamics.

Today, we are just now getting to the point where you can properly evaluate the track records of firms that emerged in the last 15 years like First Round Capital, Founders Fund, Thrive Capital, a16z, and others.

Returns are a Point in Time

Why are track records and performance so complicated? Well, returns are a point in time and company performance is rarely linear.

a16z and Scott Kupor published an excellent piece related to this point several years ago titled, “When Is a “Mark” Not a Mark? When It’s a Venture Capital Mark.” It’s worth re-reading if you have the time. It is another reminder that there is a lot of nuance in track records. Not only are valuations a point in time, but not all valuations are the same (see Scott’s comments on owning common equity versus preferred). Scott’s conclusion is the right one:

Venture capital is a long game. Calling the outcome on funds that are less than 5 years old, where many of the portfolio companies haven’t even shipped their products, based on non-uniform, point-in-time valuation metrics, is like reporting the Super Bowl winner based on the result of pre-season NFL games or even training camp scrimmages. At best, it’s off the mark.

Let’s take Scott’s point one step further by examining the last reported valuation of three very different, but successful companies.3 The dashed grey line indicates a $1b post-money valuation while the blue line represents the most recent post-money valuation. Any guesses on the companies?

As you can see, venture capital is indeed a long game. A VERY long game to be exact. These companies took anywhere from eight to thirteen years to cross a $1b post-money valuation. I’ve certainly cherry-picked these examples, and the market seems to be accelerating with companies like Clubhouse, Hopin, and others raising at $1b+ valuations within a couple of years of founding, but you get the idea.

Company A - Twitch

Twitch is memorialized in the track records of Y Combinator, Bessemer, Alsop Louie, and Thrive as a $970M exit. Today, it is still technically “marked” at a $970M valuation in the track records of those firms. However, I would argue that Twitch is a generational company and if it were spun out of Amazon it would be worth many, many multiples of its acquisition price in the current market. Now you might say this is an obvious point and we could make a similar case about a ton of other companies like Venmo, Braintree, Oculus, Duo Security, WhatsApp, or any number of tech acquisitions the past 15 years.4 You would be right and that’s the point. How should LPs think about this dynamic since VCs are minority investors and often don’t control the sale process?

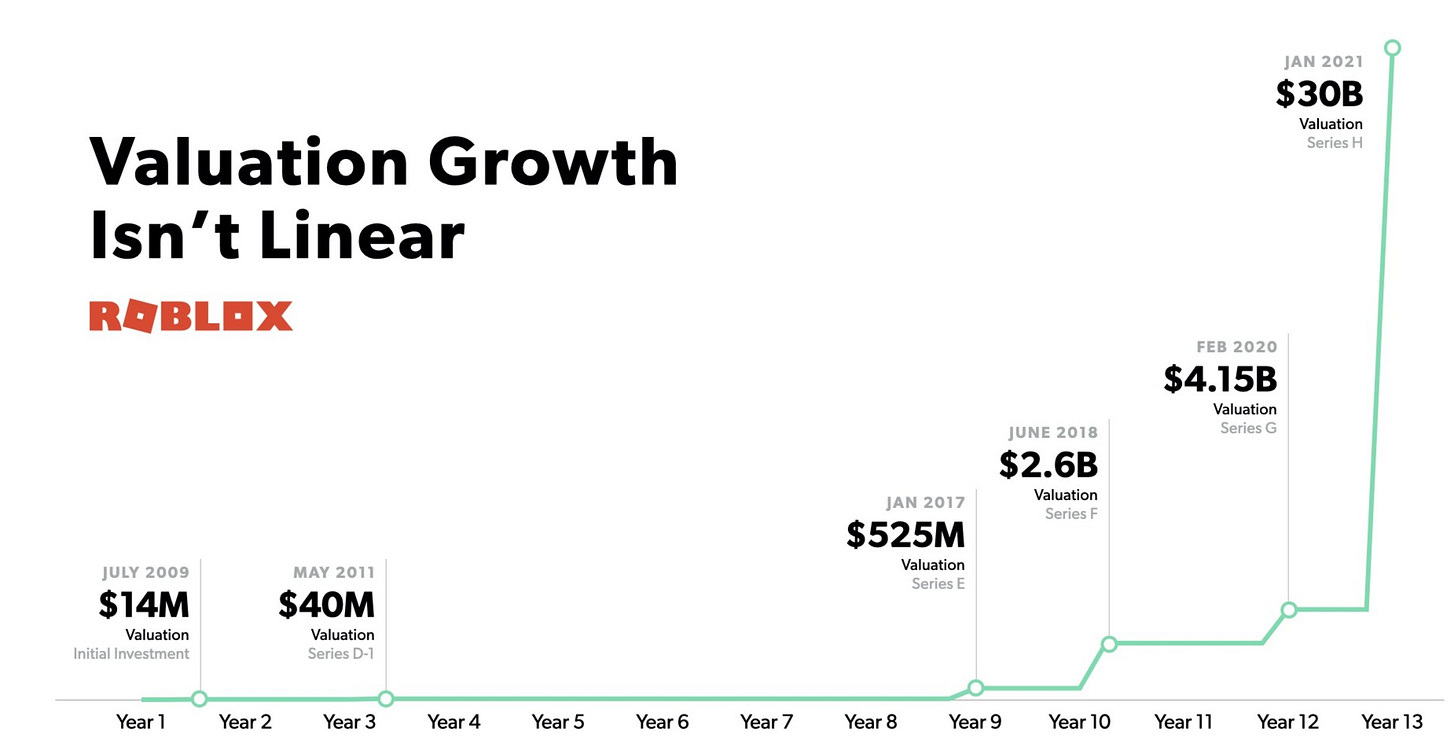

Company B - Roblox

Roblox’s IPO partially inspired this post. The company was a 13-year overnight success. I encourage you to read Chris Fralic’s reflections on Roblox.

The lesson here is that it takes a long time to build a transcendent company, and you’ll often be misunderstood or undervalued for most of that time.

In June 2018, FRC’s stake in Roblox was worth roughly $160M (6.3% ownership at IPO). In January 2021, FRC’s stake in Roblox was worth roughly $1.9B! That is a massive difference in just two and a half years. Returns are a point in time.

Now imagine this same exercise for Altos Ventures who had both Coupang and Roblox (21% ownership) go public in 2021. My guess, and I haven’t seen the numbers, is Altos is probably one of the best-performing venture capital firms of the past decade with more great outcomes on the way.

Company C - Shopify

Shopify went public in 2015 at a little under a $2B market cap. Today, Shopify trades at nearly a $200B market cap! Unfortunately, and again I don’t know this for certain, the vast majority of that appreciation didn’t accrue to Shopify’s venture investors (Bessemer Venture Partners, FirstMark Capital, and OMERS Ventures). My guess is that those firms realized their return on Shopify within a couple of years of the IPO which would be typical for most venture capital investors as VCs often liquidate their public holdings by distributing shares (otherwise known as an in-kind distribution which allows each investor to make their own hold versus sell decision after receiving the shares).5 However, one of the benefits of in-kind distributions is that it allows GPs to continue to hold shares that they receive from their carried interest distributions. Again, I don’t know for certain, but there are probably Partners at those firms who held their $SHOP shares for many years. If so, how should LPs think about that decision? Should that factor into a track record?

The point of highlighting Shopify and Twitch is that they are transcendent companies, but the track records of its venture capital investors probably don’t fully capture that reality for different reasons. For me, the quality of outcomes, decision-making, and business models matter just as much as the track record on the page.

Summary

In an asset class that is based almost entirely on the future, I would argue that despite the academic literature and conventional wisdom, track records provide limited partners with little signal. And by the time that signal is valuable, allocations are probably too scarce to be meaningful. The dynamics on the field change too frequently for there to be a lot of signals in a relatively short period of time.

To sum it all up, I’ll leave you with a great quote from Chris Duovos at Ahoy Capital:

When we make an investment, we're investing into a blind pool. People sell their track record - but as attractive as that might be, the leap we're making is that past performance is indicative of future success. Sometimes it is, but sometimes it isn't for a variety of reasons (luck, changing strategy, changing motivations, market changes, etc).

If you were overly focused on track records the past 10 years you would’ve missed numerous promising emerging managers and an entirely new generation of solo capitalists. Put differently, I wouldn’t want to be backward-looking in a forward-looking asset class.

Track records are about assessing process, decision quality, business quality, repeatability, etc. For VCs, both new and emerging, it is important to communicate that to your LPs. In Gil Dibner’s words, “provide evidence of something systematic.” Everyone should be able to answer this question:

What is it that gives you or your firm the ability to consistantly identify and partner with transcendent companies and entrepreneurs every vintage?

It can be your network, culture, partnership dynamics, thematic approach, process, captive resources, value-add, etc. It’s hard, and not everyone will believe you, but that’s what most LPs are searching for at the end of the day.

My hope is to explore this idea more in a future post and provide some other ideas that might serve as interim signals. For now, please let me know if you have any thoughts or comments.

Preview

A very fair criticism of my initial draft was that I didn’t provide a framework for other forward-looking signals. I’ve touched a bit on some of these signals in prior posts (Brand-to-AUM Ratio), but my hope is to go deeper on this topic. For now, I’ll leave you with one signal that I think about which is “transitive track record” (h/t to Gil Dibner for this name) — the percentage of companies that have raised follow-on rounds from firms or partners with “trustable decision-making.” It’s a VERY imperfect measure when used in isolation, and my list of “trustable” firms or partners will differ from another investor, but it can be a helpful tool when evaluating early-stage managers, especially those managers that I don’t know well. More on this in a later post.

Other Links

📌 Mark Suster’s follow-up to the NYT’s article on a16z’s returns (Link). Mark nailed it in his post. Very prescient in hindsight.

Oper8r on sharing your track record as an emerging manager (Link)

Chris Duovos on repeatability (Link)

Follow up | [No. 3] Brand and AUM

The feedback on the last post was excellent and a great reminder of why I decided to start this Substack. I’ve included several comments from folks below that I thought were worth highlighting:

“…VC brands are "unaided awareness" in the entrepreneur. In other words, if I'm an entrepreneur, who immediately comes to mind as the best backer for my kind of business” - David Landry, Demesne Investments

“Reputation arrives on foot, and leaves on horseback”

“You have to earn the right” - Mike Smith, Footwork Capital

“Earn the right through conviction and product strength to support great founders, teams and missions” - Roger Ehrenberg, IA Ventures

My favorite was this tweet from Sundeep Peechu at Felicis Ventures. That’s it. That was my post in 240 characters or less. What’s the quote about writing a long letter because I didn’t have time to write a short one?

Thank you to the folks on Twitter like Myles Danielson, Gil Dibner, Itai Tsiddon, Zal Bilimoria, Samir Kaji, Michael Dempsey, Dan Kimerling, Laura Roller, and others for offering to read drafts of this post and providing feedback. You all made this post better and pushed my thinking forward. It is a great reminder to me why there is value in learning in public 🙏.

Top quartile venture funds tend to repeat top quartile performance 45% of the time. The paper confirms the findings in both pre and post-2000 funds through 2014. I think one issue I have with the conclusions is that from 2009 to 2020 we’ve been operating in the same cycle that has rewarded “risk-taking and velocity”. Harris et al. “Has Persistence Persisted in Private Equity? Evidence from Buyout and Venture Capital Funds” accessed at https://bfi.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/BFI_WP_2020167.pdf.

Annie Duke’s “Thinking in Bets” is the best investment book I’ve read. It should be required reading for anyone in the investment profession. https://amzn.to/3zSlZ1N

Gil Dibner at Angular Ventures rightfully noted that from here this post starts to focus on single asset narratives versus an aggregate track record or distribution of outcomes. While I’ve used these companies to make my point, track records are about dollars returned to LPs, not billion-dollar valuations.

The WhatsApp acquisition was $5B in cash and $12B in stock. Do you include the share price appreciation in Sequoia’s track record? Should you? Why or why not? This stuff is hard.

In practice, most institutional LPs aren’t equipped to make hold versus sell decisions on a specific stock so they often liquidate the stock in an orderly manner after distribution. There are also issues around GPs recommending a liquidation strategy which further complicates the decision for LPs)